From Quad Axel to Surgery: What Figure Skating Teaches Us about Psychomotor Skill Development

[First published in LinkedIn. This is a backup copy.]

Ilia Malinin, the reigning world champion and American figure skating sensation, also the self-proclaimed “quadgod,” can spin 1620° in midair. That is four and a half full rotations off the ground. He made history by landing the first-ever quadruple axel in competition.

“How does he do that?” is a question both fans and competitors ask with awe.

Of course, Ilia is an elite athlete. But I am not here to dissect world-class athleticism. What I’m after is the learning and instruction of psychomotor skills, because the same educational principles matter beyond sports, in healthcare, aviation, skilled trades, performing arts, and emerging tech.

Psychomotor skills are core competencies of professions where movement, precision, and timing are key. They are developed often through performance-based assessments, simulations, and even gamified learning and often under pressure, where the accuracy of performances is critical.

Why Instructional Designers Should Care About the Psychomotor Domain

This writing extends some excellent ideas raised by Luke Hobson, EdD‘s article on the psychomotor domain in instructional design. Luke reviewed taxonomies developed in the 60s and 70s and identified some possible gaps:

- The psychomotor domain is under-researched and is often seen as the “poor cousin” of the cognitive domain.

- It’s challenging to assess physical skills using traditional academic measures.

- There’s no Bloom’s-style taxonomy that’s widely adopted.

The Development of Physical Skills: Instruction in the Psychomotor Domain (Romiszowski)

To expand on Luke’s research, I will point to some thought leaders and renowned scholars in the field of instructional design who have written about the topic.

Enter Alexander Romiszowski, whose theory, The Development of Physical Skills: Instruction in the Psychomotor Domain, is documented in the second volume of Charles Reigeluth’s (1999) Instructional-Design Theories and Models book series.

In 2009, Romi, as we affectionately addressed him in graduate school, updated this theory in the third volume of Reigeluth’s book series, calling it the Skill Development Outcomes (2009) Theory. Romi presented an elegant theory that outlined the process of psychomotor skill development through systematic instructional design.

Key Highlights of Romi’s Theory

- Integration of Domains. Romi emphasized that effective instruction of physical skills must integrate the psychomotor, cognitive (understanding the skill), and affective (attitudinal) domains to ensure comprehensive learning.

- Five Stages of Skill Development. They are knowledge acquisition, execution, transfer of control, automatization, and generalization of skill.

- The Skill Acquisition Process integrates instructional strategies with feedback mechanisms (timely and specific feedback) and mental practice. Romi highlighted the value of mental rehearsal, where learners visualize performing the skill as this enhances neural pathways associated with the physical execution. Check out this YouTube shorton how figure skaters envision their moves.

- Reproductive to Productive Skills Continuum. Instructional strategies differ significantly depending on where a task sits on this continuum. For instance, to impart essential knowledge content (cognitive domain), expository teaching could be sufficient to develop reproductive skills (predictable standard procedural skills), but to develop productive skills (situation-specific application of principles and strategies), experiential methods are preferred.

- Four Domains of Skilled Activity. Romi’s model consists of the following: cognitive, psychomotor, reactive, interactive skills.

One critique of the theory is that Romi doesn’t explore learner attributes (personality, intellect, etc.) in his theory. For more details, check out this paper by Hajaraih, Bell, Pelligrini and Tahir (2012).

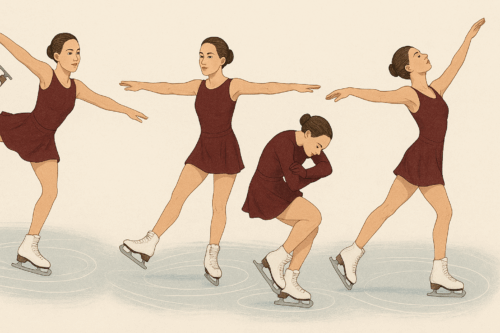

What Figure Skating Can Teach Us About Skill Assessment

Let’s go back to the rink to illustrate what an assessment of psychomotor skills could look like.

Figure skating uses a rubric-based performance assessment system which is very much in line with how we might assess psychomotor skills in other fields.

Skaters are judged using the International Judging System (IJS) which has two core components: the Technical Elements Score (TES) and the Program Components Score (PCS). This system integrates the following key elements of psychomotor skill assessment:

- Observable behavior

- Mastery level

- Technical difficulty

- Execution quality

- Expression (affective overlay)

Technical Elements Score (TES)

The technical panelists judge skaters purely on their psychomotor skills: what was performed. They identify raw motor skills and see if skaters demonstrate and can execute these skills:

- Type and difficulty of jumps (e.g., axel, quad)

- Takeoff and landing mechanics

- Spin positions and revolutions

- Footwork, edge quality, and transitions

Judges use instant replay, slow motion, and detailed criteria to confirm execution. E.g., did the blade fully rotate? Was the landing clean? Skaters have been penalized for under rotations.

Program Components Score (PCS)

This score includes more affective and expressive criteria:

- Skating skills

- Choreography and interpretation

- Overall presentation and artistry

Implications for Workforce Training

So what can we, as instructional designers, learn from the field of figure skating?

Psychomotor skill training in the workforce (think surgery, CPR, piloting, welding) should start with a competency analysis followed by the development of clear rubrics of performance competencies detailing the required criteria (novice to expert). These performance assessments must be anchored in observable behaviors. Once the evidence of learning is established, the design of appropriate learner-centered instructional strategies can be formulated.

Muscle Memory in Critical Professions

In the recent world figure-skating championships in Boston, Ilia planned to do seven quads but landed six. During interviews after winning his second world title, he said,

“I was so nervous that I couldn’t really think about anything, and I did most of my jumps with just muscle memory. But I was still able to succeed, so it made me more confident about my muscle memory.” (The Ilia Society, 2024).

What Ilia describes is the end result of highly structured and intense training. Consistent practice over time leads to automatization of the skill which produces muscle memory that we can rely on in times of stress. I believe that’s what we must aim for in fields where split-second decisions and precision save lives or ensure success.

So the essential question is: How do we help learners develop the kind of muscle memory that professionals can rely on when it matters most?

References

Malinin, I. (n.d.). Ilia Malinin.

Mohd Hajaraih, Syahidatul Khafizah. (2012). Skill Development Theory and Educational Game Design: An Integrated Design Framework. 2012 AECT International Convention Conference Paper.

Romiszowski, A. (2009). Fostering Skill Development Outcomes. in Reigeluth, Charles M. (Eds.), Instructional-design theories and models (pp. 199-224). New York: Routledge.

The Ilia Society [@TheIliaSociety]. (2024, April 4). “I was so nervous that I couldn’t really think about anything, and I did most of my jumps with just muscle memory…” [Tweet]. X (formerly Twitter). https://x.com/TheIliaSociety/status/1908547556633874921