Crafting a Learning-Centered Syllabus

Every course design is philosophy and belief in action. –Manifesto for Teaching Online, written by teachers and researchers in online education, University of Edinburgh 2011

[This was first posted in Engaged Learning blog, another blog I maintain for work. This is a companion blog post to the eLearning Bulletin Board Poster on the 4th Floor of Wohlers Hall, College of Business at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The poster is an abridged version of what a motivational syllabus looks like. It is intended to serve as a discussion stimulus only.]

As instructors, we may not be conscious of this when we are busy planning and teaching our courses, but our courses reflect our educational philosophy, and us. The first step to setting the appropriate tone for our classes is the design of an effective syllabus.

- A syllabus is, at its heart, a learning resource; a motivational introduction and guide to a great learning experience, not a legal document or Terms of Service Agreement (think software license). Sound welcoming and conversational. Address your learners in the second person pronoun (“You”). Ask, “What is the tone of my syllabus? (Approachable or defensive?)

- Include your teaching philosophy and approach to learning. Ask, “How would I make my syllabus an invitation to a great learning experience students wouldn’t want to miss? How would my syllabus help students see that they have the opportunity to develop learning skills that are applicable beyond my class?”

- Explain the rationale of activities in the course. Help students see the relevance of what they are asked to do. Ask, “What is worth learning? Why?”

- A syllabus is sometimes seen as a learning contract between the instructor and the students; hence expectations from both sides are communicated. Ask, “What can you (learners) expect from me (e.g. communication and feedback/grading turnaround time)?” Next, instead of telling students what you expect from them, provide learners with the opportunity to tell you what they expect from their peers (other learners). On the first day of class, conduct this learning activity with your students (Singham in Weimer, 2010). Pose two questions to learners. Ask, “What do you expect from an instructor who is giving 100% to the course?” and “What would you expect to see your peers doing if they were giving 100% to the course?” Using these responses, edit your syllabus on your learner expectations. This helps students see that they have a part to play in making this course a successful one and gives them some ownership in course decision-making. We are co-learners in the learning experience.

- Include an assessment table in your syllabus that is linked to course goals, assignments, grades (percentage) and the rubrics (Crossman, 2014). Placed together, these help students to see that there is alignment in course learning objectives, assignments and rubrics and that the syllabus is a useful resource for them. Ask, “How can I align my course activities and assessments with the course goals and communicate that to my students?”

- Incorporate the syllabus as a learning resource for class meetings/live sessions so that students will learn to use it regularly. Some instructors include module/weekly agendas in their syllabus; others include resources for regular references (Crossman, 2014). Ask, “How can I make my syllabus a useful learning resource?”

- A syllabus also has to meet university and department guidelines. There are components that must be present in a syllabus: Accommodations statement to support learners with special educational needs; Academic Integrity or University Honor Code; Grading Policy; Course Prerequisites (for some courses). Ask, “How can I communicate these policies in a firm but humane way without sounding authoritarian?”

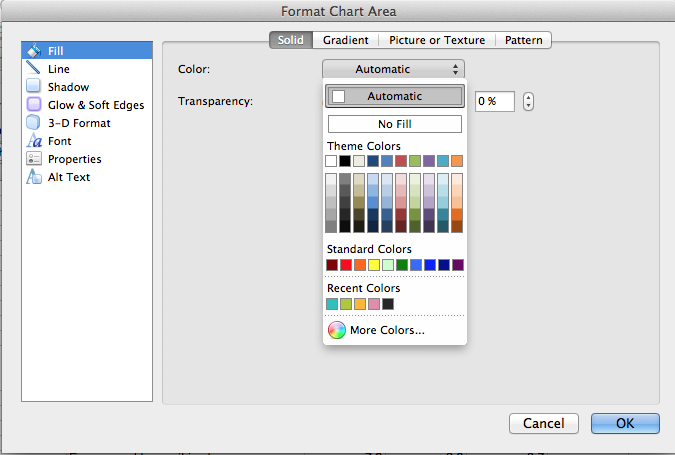

- Format it in such a way that it is as appealing and as accessible as possible to learners. Ask, “What breaks the monotony of texts and can be conveyed graphically without losing meaning?”

References and Resources:

Carnegie Mellon University Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and Educational Innovation. (2015). Samples of creative syllabi.

Cornell University’s Center for Teaching Excellence. (2017, Aug. 4). Writing a syllabus. [Great resources on the what, how and why of effective syllabus design, including a syllabus template with essential components]

Crossman, J. M. (2014, Jun. 9). Using the syllabus as a learning resource. Faculty Focus.

Everett Community College. (n.d.). Sample syllabus statements regarding accommodations.

Halliday, A. (2014, Nov. 28). Lynda Barry’s wonderfully illustrated syllabus & homework assignments from her UW-Madison class, “The Unthinkable Mind. [Suitable for more arts-based disciplines; a text-only version is required for accessibility]

Jones, J. B. (2011, Aug. 26). Creative approaches to the syllabus. ProfHacker in The Chronicle of Higher Education. [Note: Embedded in this post are links to alternative formats for syllabus design – e.g. graphical displays of learning objectives]

Pacansky-Brock, M. (2017). Humanized syllabus (The History of Still Photography). [Includes a link to her full project site]

Paff, L. (2016, Dec. 1). Preparing a learner-centered syllabus. Faculty Focus Premium subscribers only.

Weimer, M. (2010, Mar. 23). What students expect from instructors, other students. Faculty Focus.